Crosswind Landing Techniques Part One - Crab and Sideslip

/This video very clearly illustrates my point that landing in a strong crosswind can be a challenging and in some cases downright dangerous (Video © CargoSpotter (with thanks); courtesy U-Tube).

Generally, flight crews use one of two techniques or a combination thereof to approach and land in crosswind conditions. If winds exceed aircraft tolerances, which in the 737-800 is 33 knots (winglets) and 36 knots (no winglets), the flight crew will divert to their alternate airport (Brady, Chris - The Boeing 737 technical Guide).

crab approach. Wind is right to left at 16 knots with aircraft crabbing into the wind to maintain centerline approach course. Just before flare, left rudder will be applied to correct for drift to bring aircraft into line with centerline of runway. This technique is called 'de-crabbing’. During such an approach, the right wing may also be lowered 'a tad' (cross-control) to ensure that the aircraft maintains the correct alignment and is not blown of course by a 'too-early de-crab'. Right wing down also ensures the main gear adheres to the runway during the roll out

Maximum crosswind figures can differ between airlines and often it's left to the pilot's discretion and experience. Below is an excerpt from the Landing Crosswind Guidelines from the Flight Crew Training Manual (FCTM). Note that FCTMs can differ depending on date of publication.

There are several factors that require careful consideration before selecting an appropriate crosswind technique: the geometry of the aircraft (engine and wing-tip contact and tail-strike contact), the roll and yaw authority of the aircraft, and the magnitude of the crosswind component. Consideration also needs to be made concerning the effect of the selected technique when the aircraft is flared to land.

Crosswind Approach and Landing Techniques

There are four techniques used during the approach and landing phase which center around the crab and sideslip approach. The crab and sideslip are the primary methods and most commonly used while the de-crab and combination crab-sideslip are subsets that can be used when crosswinds are stronger than usual.

It must be remembered that whatever method is used it is at the discretion of the pilot in command.

Crab (to touchdown).

Sideslip (wing low).

De-crab during flare.

Combination crab and sideslip.

1: Crab (to touchdown)

Airplane maintains a crab during the final approach phase.

Airplane touches down in crab.

Flight deck is over upwind side of runway (Main gear is on runway center).

Airplane will de-crab at touchdown.

Flight crew must maintain directional control during roll out with rudder and aileron.

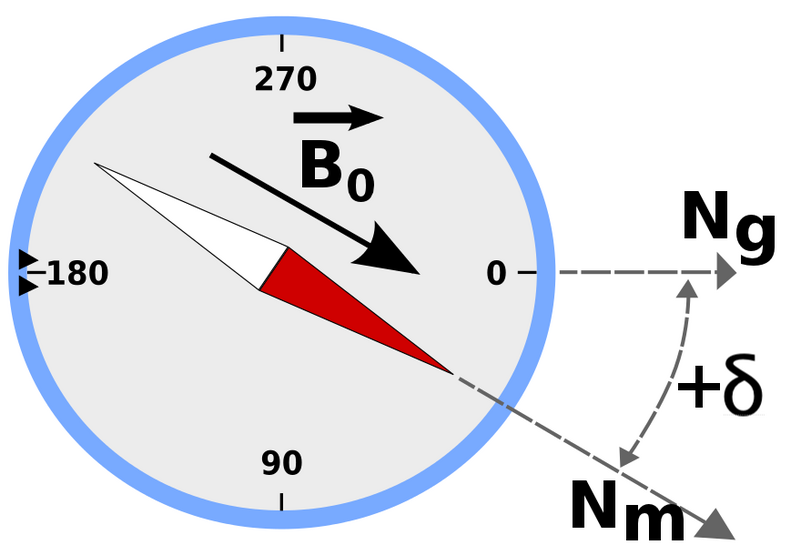

With wings level, the crew will use drift correction to counter the effect of the crosswind during approach. Drift correction will cause the aircraft to be pointing in a direction either left or right of the runway heading, however, the forward energy of the aircraft will be towards the centerline. This is called the crab because the aircraft is crabbing at an angle left or right of the aircraft's primary heading.

Most jetliners have the ability to land in a crab, however, it must be remembered that landing in a crab places considerable stress on the main landing gear and tyre side-walls, which in turn can cause issues with tyre and wheel damage, not too mention directional control.

The later is caused by the tandem arrangement of the main landing gear that has a strong tendency to travel in the direction that the nose of the aircraft is pointing at the moment of touchdown. This can result in the aircraft travelling toward the edge of the runway during the roll out. To counter this, and align the nose of the aircraft with the centreline of the runway, the pilot flying must apply rudder input when lowering the nose wheel to the runway surface.

A reference to the maximum amount of crab that can be safely applied in the B737 was not found, other than maximum crosswind guidelines must not be exceeded. The crab touchdown technique is the preferred choice if the runway is wet.

2: Sideslip (wing low)

Upwind wing lowered into wind.

Opposite rudder (downwind direction) maintains runway alignment.

In a sideslip the aircraft will be directly aligned with the runway centerline using a combination of into-wind aileron and opposite rudder control (called cross-controls) to correct the crosswind drift.

The pilot flying establishes a steady sideslip (on final approach by applying downwind rudder to align the airplane with the runway centerline and upwind aileron to lower the wing into the wind to prevent drift. The upwind wheels should touch down before the downwind wheels touch down.

The sideslip technique reduces the maximum crosswind capability based on a 2/3 ratio leaving the last third for gusts. However, a possible problem associated with this approach technique is that gusty conditions during the final phase of the landing may preempt a nacelle or wing strike on the runway.

Therefore a sideslip landing is not recommended when the crosswind component is in excess of 17 knots at flaps 15, 20 and 30, or 23 knots at flaps 40.

The sideslip approach and landing can be challenging both mentally and physically on the pilot flying and it is often difficult to maintain the cross control coordination through the final phase of the approach to touchdown. If the flight crew elects to fly the sideslip to touchdown, it may also be necessary to add a crab during strong crosswinds.

3: De-crab During Flare(with removal of crab during flare)

Maintain crab on the approach.

At ~100 foot AGL the flight crew will de-crab the aircraft; and,

During the flare, apply rudder to align airplane with runway centreline and, if required slight opposite aileron to keep the wings level and stop roll.

This technique is probably the most common technique used and is often referred to as the 'crab-de-crab'.

The crab technique involves establishing a wings level crab angle on final approach that is sufficient to track the extended runway centerline. At approximately 100 foot AGL and during the flare the throttles are reduced to idle and downwind rudder is applied to align the aircraft with the centerline (de-crab).

Depending upon the strength of the crosswind, the aircraft may yaw when the rudder is applied causing the aircraft to roll. if this occurs, the upwind aileron must be placed into the wind and the touchdown maintained with crossed controls to maintain wings level (this then becomes a combination crab/sideslip - point 4).

Upwind aileron control is important, as a moderate crosswind may generate lift by targeting the underside of the wing. Upwind aileron control assists in ensuring positive adhesion of the landing gear to the runway on the upwind side of the aircraft as the wind causes the wing to be pushed downwards toward the ground.

Applied correctly, this technique results in the airplane touching down simultaneously on both main landing gear with the airplane aligned with the runway centerline.

4: Combination Crab and Sideslip

De-crab using rudder to align aircraft with runway (same as point 3 de crab during flare).

Application of opposite aileron to keep the wings level and stop roll (sideslip).

The technique is to maintain the approach in a crab, then during the final stages of the approach and flare increase the into-wind aileron and land on the upwind tyre with the upwind wing slightly low. The combination of into-wind aileron and opposite rudder control means that the flight crew will be landing with cross-controls.

The combination of crab and sideslip is used to counter against the turbulence often associated with stronger than normal crosswinds.

As with the sideslip method, there is the possibility of a nacelle or wing strike should a strong gust occur during the final landing phase, especially with aircraft in which the engines are mounted beneath the wings.

FIGURE 1: Diagram showing most commonly used approach techniques (copyright Boeing)

Operational Requirements and Handling Techniques

With a relatively light crosswind (15-20 knot crosswind component), a safe crosswind landing can be conducted with either; a steady sideslip (no crab) or a wings level, with no de-crab prior to touchdown.

With a strong crosswind (above a 15 to 20 knot crosswind component), a safe crosswind landing requires a crabbed approach and a partial de-crab prior to touchdown.

For most transport category aircraft, touching down with a five-degree crab angle with an associated five-degree wing bank angle is a typical technique in strong crosswinds.

The choice of handling technique is subjective and is based on the prevailing crosswind component and on factors such as; wind gusts, runway length and surface condition, aircraft type and weight, and crew experience.

Touchdown Recommendations

No matter which technique used for landing in a crosswind, after the main landing gear touches down and the wheels begin to rotate, the aircraft is influenced by the laws of ground dynamics.

Effect of Wind Striking the Fuselage, Use of Reverse Thrust and Effect of Braking

The side force created by a crosswind striking the fuselage and control surfaces tends to cause the aircraft to skid sideways off the centerline. This can make directional control challenging.

Reverse Thrust

The effects of applying the reverse thrust, especially during a crab ‘only’ landing can cause additional direction forces. Reverse thrust will apply a stopping force aligned with the aircraft’s direction of travel (the engines point in the same direction as the nose of the aircraft). This force increases the aircraft’s tendency to skid sideways.

Effects of Braking

Autobrakes operate by the amount of direct pressure applied to the wheels. In a strong crosswind landing, it is common practice to use a combination of crab and sideslip to land the aircraft on the centerline. Sideslip and cross-control causes the upwind wing to be slightly down upon landing and this procedure is carried through the landing roll to control directional movement of the aircraft.

The extra pressure applied to the ‘wing-down’ landing gear causes increased auto-braking force to be applied which creates the tendency of the aircraft to turn into the wind during the landing roll. Therefore, a flight crew must be vigilant and be prepared to counter this unwanted directional force.

If the runway is contaminated and contamination is not evenly distributed, the anti-skid system may prematurely release the brakes on one side causing further directional movement.

FIGURE 2: Diagram showing recovery of a skid caused by crosswind and reverse thrust side forces (source: Flight Safety Foundation ALAR Task Force)

Maintaining Control - braking and reverse thrust

If the aircraft tends to skew towards the side from higher than normal wheel-braking force, the flight crew should release the brakes (disengage autobrake) which will minimize directional movement.

To counter against the directional movement caused by application of reverse thrust, a crew can select reverse idle thrust which effectively cancels the side-force component. When the centerline has been recaptured, toe brakes can be applied and reverse thrust reactivated.

Runway Selection and Environmental Conditions

If the airport has more than one runway, the flight crew should land the airplane on the runway that has the most favourable wind conditions. Nevertheless, factors such as airport maintenance or noise abatement procedures sometime preclude this.

I have not discussed environmental considerations which come into play if the runway is wet, slippery or covered in light snow (contaminated). Contaminated conditions further reduce (usually by 5 knots) the crosswind component that an aircraft can land.

Determining Correct Landing Speed (Vref)

Vref is defined as landing speed or threshold crossing speed.

When landing with a headwind, crosswind, or tailwind the Vref must be adjusted accordingly to obtain the optimal speed at the time of touchdown. Additionally the choice to use or not use autothrottle must be considered. Failure to do this may result in the aircraft landing at a non-optimal speed causing runway overshoot, stall, or floating (ground affect).

This article is part one of two posts. The second post addresses the calculations required to safety land in crosswind conditions: Crosswind Landing Techniques Part Two Calculations.