VNAV 'Gotchas' - Avoiding Unwanted Level-Offs

/One aspect of using VNAV during published instrument departures, arrivals, and approaches is that it can cause unnecessary level-offs.

These level-offs can cause engines to spool needlessly, increase fuel cost and stagger a Continuous Descent Final Approach (CDFA) such as when executing an RNAV approach.

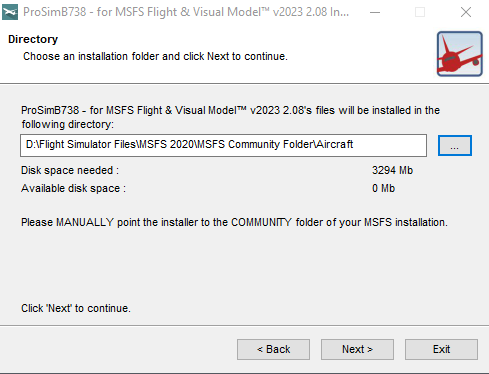

It is not only domestic airliners that must meet altitude constraints; military aircraft also must meet the same requirements when landing at a non-military airport (click to enlarge). Image is copyright xairforces.net. For those interested in flying the Wedgetail, there is a model available for ProSim-AR users on their forum page.

To avoid this, and ensure that minimum altitude constraints are met, two techniques can be used.

METHOD 1: Constraints Are Not Closely Spaced.

This technique is normally used when waypoints with altitude constraints are not closely spaced (in other words, there is a moderate distance between altitude constraints).

During climbs, the maximum or hard altitude constraints should be set in the Mode Control Panel (MCP).

Minimum crossing altitudes need not be set in the MCP as the FMC message function will alert the crew if these constraints cannot be satisfied.

During descent, the MCP altitude is set to the next constraint or clearance altitude, whichever will be reached first.

Immediately prior to reaching the constraint, when compliance with the constraint is assured, and when cleared to the next constraint, the MCP altitude is reset to the next constraint/altitude level.

METHOD 2: Constraints Are Closely Spaced.

Where constraints are closely spaced to the extent that crew workload is adversely affected, and unwanted level-offs maybe a concern, the following is approved:

For departures, set the highest of the closely-spaced constraints.

For arrivals, initially set the lowest of the closely-spaced altitude constraints or the Final Approach Fix (FAF) altitude, whichever is higher.

IMPORTANT: When using either technique, the FMS generated path should be checked against each altitude constraint displayed in the CDU to ensure that the path complies with all constraints. Furthermore, the selection of a pitch mode other than VNAV PTH or VNAV SPD should be avoided, as this will result in the potential violation of altitude constraints.

To enlarge more on VNAV is beyond the scope of this post. A future post will address this topic in more detail.

Crew Controls Automation - Not Vice Versa

However, the system is only as good as the knowledge of the person pushing the buttons. It is very important that a flight crew control the automation rather than the automation control the flight crew.

If VNAV begins to do something that is unplanned or unexpected, do not spend precious time ‘thinking about the reasons why’ – disconnect VNAV and use a more traditional method or hand floy the aircraft. Then, determine why VNAV did what it did. The most common comment heard in today's modern cockpits is ‘What is it doing now…’

Final Call

VNAV is an easy concept to understand, but it can be confusing due to innumerable variables associated with vertical navigation. VNAV is probably one of the more complicated systems that virtual and real pilots alike have to understand. When using VNAV it is paramount to maintain vigilance on what it is doing at any one time, especially during descent and final approach. Furthermore, it is good airmanship to always have a redundancy plan in place – a ‘what if’ should VNAV fail to do what was anticipated.

The below article also discuss VNAV:

An interesting article concerning VNAV:

Acronyms and Glossary

CDU - Control Display Unit (aka FMC)

FAF – Final Approach Fix

FMC - Flight Management Computer

FMS - Flight Management System. Supply of data to the FMC and CDU

Gotcha - An annoying or unfavorable feature of a product or item that has not been fully disclosed or is not obvious.

LNAV – Lateral Navigation

MCP – Mode Control Panel

NPA - Non Precision Approach

VNAV – Vertical Navigation

VNAV PTH – Vertical Navigation Path

VNAV SPD – Vertical Navigation Speed