Throttle Quadrant Rebuild - Clutch, Motors, and Potentiometers

/Captain-side of throttle quadrant showing an overview of the new design. The clutch assembly, motors, and string potentiometer can be seen, in addition to a portion of the revised parking brake mechanism

An earlier article, Throttle Quadrant Rebuild – Evolution Has Led to Major Changes has outlined the main changes that have been made to the throttle quadrant during the rebuild process.

This article will add detail and explain the decision making process behind the changes and the advantages they provide. As such, a very brief overview of the earlier system will be made followed by an examination of the replacement system.

Limitation

It is not my intent to become bogged down in infinite detail; this would only serve to make the posts very long, complicated and difficult to understand, as the conversion of a throttle unit is not simplistic.

This said, the provided information should be enough to enable you to assimilate ideas that can be used in your project. I hope you understand the reasoning for this decision.

The process of documenting the throttle quadrant rebuild will be recorded in a number of articles. In his article I will discuss the clutch assembly, motors, and potentiometers.

Why Rebuild The Throttle Quadrant

Put bluntly, the earlier conversion had several problems; there were shortfalls that needed improvement, and when work commenced to rectify these problems, it became apparent that it would be easier to begin again rather than retrofit. Moreover, the alterations spurred the design and development of two additional interface modules that control how the throttle quadrant was to be connected with the simulator.

TIM houses the interface cards responsible for the throttle operation while the TCM provides a communication gateway between TIM and the throttle.

Motor and Clutch Assembly - Poor Design (in previous conversion)

The previous throttle conversion used an inexpensive 12 volt motor to power the thrust lever handles forward and aft. Prior to being used in the simulator, the motors were used to power electric automobile windows. To move the thrust lever handles, an automobile fan belt was used to connect to a home-made clutch assembly.

This system was sourly lacking in that the fan belt continually slipped. Likewise, the nut on the clutch assembly, designed to loosen or tighten the control on the fan belt, was either too tight or too loose - a happy medium was not possible. Furthermore, the operation of the throttle caused the clutch nut to continually become loose requiring frequent adjustment.

The 12 volt motors, although suitable, were not designed to entertain the precision needed to synchronize the movement of the thrust levers; they were designed to push a window either up or down at a predefined speed on an automobile.

The torque produced from these motors was too great, and the physical backlash when the drive shaft moved was unacceptable. The backlash transferred to the thrust levers causing the levers to jerk (jump) when the automation took control (google motor backlash).

This system was removed from the throttle. Its replacement incorporated two commercial motors professionally attached to a clutch system using slipper clutches.

Close up image of the aluminium bar and ninety degree flange attachment. The long-threaded screw connects with the tail of the respective thrust lever handle. An identical attachment at the end of the screw connects the screw to the large cog wheel that the thrust lever handles are attached

Clutch Assembly, Connection Bars and Slipper Clutches - New Design

Mounted to the floor of the throttle quadrant are two clutch assemblies (mounted beside each other) – one clutch assembly controls the Captain-side thrust lever handle while the other controls the First officer-side.

Each assembly connects to the drive shaft of a respective motor and includes in its design a slipper clutch. Each clutch assembly then connects to the respective thrust lever handle. A wiring lumen connects the clutch assembly with each motor and a dedicated 12 volt power supply (mounted forward of the throttle quadrant). See above image.

Connection Bars

diagram 1: crossection and a cut-away of a slipper clutch

To connect each clutch assembly to the respective thrust lever handle, two pieces of aluminium bar were engineered to fit over and attach to the shaft of each clutch assembly.

Each metal bar connects to one of two long-threaded screws, which in turn connect directly with the tail of each thrust lever handle mounted to the main cog wheel in the throttle quadrant.

Slipper Clutches

close up of slipper clutch showing precision ball bearings

A slipper clutch is a small mechanical device made from tempered steel, brass and aluminum. The clutch consists of tensioned springs sandwiched between brass plates and interfaced with stainless-steel bearings. The bearings enable ease of movement and ensure a long trouble-free life.

The adjustable springs are used to maintain constant pressure on the friction plates assuring constant torque is always applied to the clutch. This controls any intermittent, continuous or overload slip.

A major advantage, other than their small size, is the ease at which the slipper clutches can be sandwiched into a clutch assembly.

Anatomy and Key Advantages of a Slipper Clutch

A number of manufacturers produce slipper clutches that are specific to a particular industry application, and while it's possible that a particular clutch will suit the purpose required, it's probably a better idea to have a slipper clutch engineered that is specific to your application.

The benefit of having a clutch engineered is that you do not have to redesign the drive mechanism used with the clutch motors.

Key advantages in using slipper clutches are:

Variable torque;

Long life (on average 30 million cycles with torque applied);

Consistent, smooth and reliable operation with no lubrication required;

Bi-directional rotation; and,

Compact size.

The clutch assembly as seen from the First Officer side of the throttle quadrant. Note the slipper clutch that is sandwiched between the assembly and the connection rods. Each thrust lever handle has a dedicated motor, slipper clutch and connection rod. The motor that powers the F/O side can be seen in the foreground

Clutch Motors

The two 12 Volt commercial-grade motors that provide the torque to drive the clutch assembly and movement of the thrust lever handles, have been specifically designed to be used with drives that incorporate slipper clutches.

In the real world, these motors are used in the railway and marine industry to drive high speed components. As such, their design and build quality is excellent. The motors are designed and made in South Korea.

Each motor is manufactured from stainless steel parts and has a gearhead actuator that enables the motor to be operated in either forward or reverse. Although the torque generated by the motor (18Nm stall torque) exceeds that required to move the thrust lever handles forward and aft, the high quality design of the motor removes all the backlash evident when using other commercial-grade motors. The end result is an extraordinary smooth, and consistent operation when the thrust lever handles move.

A further benefit using this type of motor is its size. Each motor can easily be mounted to the floor of the throttle quadrant; one motor on the Captain-side and the second motor on the First Officer-side. This enables a more streamlined build without using the traditional approach of mounting the motors on the forward firewall of the throttle quadrant.

captain-side 12 Volt motor, wiring lumen and dual string potentiometer that control thrust levers

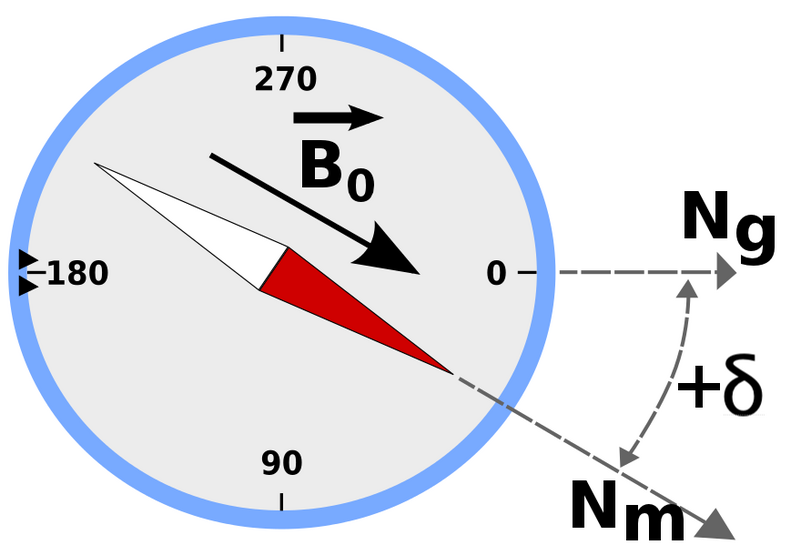

String Potentiometers - Thrust Levers 1/2

Two Bourns dual-string potentiometers have been mounted in the aft section of the throttle unit. The two potentiometers are used to accurately calibrate the position of each thrust lever handle to a defined %N1 value. The potentiometers are also used to calibrate differential reverse thrust.

The benefit of using Bourns potentiometers is that they are designed and constructed to military specification, are very durable, and are sealed. The last point is important as sealed potentiometers will not, unlike a standard potentiometer, ingest dust and dirt. This translates to zero maintenance.

Traditionally, string potentiometers have been mounted either forward or rear of the throttle quadrant; the downside being that considerable room is needed for the operational of the strings.

In this build, the potentiometers were mounted on the floor of the throttle housing (adjacent to the motors) and the dual strings connected vertically, rather than horizontally. This allowed maximum usage of the minimal space available inside the throttle unit.

Automation, Calibration and Movement

The automation of the throttle remains as it was. However, the use of motors that generate no backlash, and the improved calibration gained from using string potentiometers, has enabled a synchronised movement of both thrust lever handles which is more consistent than previously experienced.

Reverse Thrust 1/2

Micro-buttons were used in the previous conversion to enable enable reverse thrust - reverse thrust was either on or off, and it was not possible to calibrate differential reverse thrust.

Dual string potentiometer that enables accurate calibration of thrust lever handles and enables differential thrust when reversers are engaged

In the new design, the buttons have been replaced by two string potentiometers (mentioned earlier). This enables each reverse thrust lever to be accurately calibrated to provide differential reverse thrust. Additionally, because a string potentiometer has been used, the full range of movement that the reverse thrust is capable of can be used.

The video below demonstrates differential reverse thrust using theProSim737 avionics suite. The first segment displays equal reverse thrust while the second part of the video displays differential thrust.

Incremental reverse thrust N1 displayed on eicas (ProSim737) from dual potentiometer

Calibration

To correctly position the thrust lever handles in relation to %N1, calibration is done within the ProSim737 avionics software In calibration/levers, the position of each thrust lever handle is accurately ‘registered’ by moving the tab and selecting minimum and maximum. Unfortunately, this registration is rather arbitrary in that to obtain a correct setting, to ensure that both thrust lever handles are in the same position with identical %N1 outputs, the tab control must be tweaked left or right (followed by flight testing).

When tweaked correctly, the two thrust lever handles should, when the aircraft is hand-flown (manual flight), read an identical %N1 setting with both thrust levers positioned beside each other. In automated flight the %N1 is controlled by the interface card settings (Polulu JRK cards or Alpha Quadrant cards).

Have The Changes Been Worthwhile

Comparing the new system with the old is 'chalk and cheese'.

One of the main reasons for the improvement has been the benefits had from using high-end commercial-grade components. In the previous conversion, I had used inexpensive potentiometers, unbalanced motors, and hobby-grade material. Whilst this worked, the finesse needed was not there.

One of the main shortcomings in the previous conversion, was the backlash of the motors on the thrust lever handles. When the handles were positioned in the aft position and automation was engaged, the handles would jump forward out of sync. Furthermore, calibration with any degree of accuracy was very difficult, if not impossible.

The replacement motors have completely removed this backlash, while the use of string potentiometers have enabled the position of each thrust lever handle to be finely calibrated, in so far, as each lever will creep slowly forward or aft in almost perfect harmony with the other.

An additional improvement not anticipated was with the installation of the two slipper clutches. Previously, when hand-flying there was a binding feeling felt as the thrust lever handles were moved forward or aft. Traditionally, this binding has been difficult to remove with older-style clutch systems, and in its worst case, has felt as if the thrust lever handles were attached to the ratchet of a bicycle chain.

The use of high-end slipper clutches has removed much of these feeling, and the result is a more or less smooth feeling as the thrust lever handles transition across the throttle arc.

Future Articles

Future articles will address the alterations made to the speedbrake, parking brake lever, and internal wiring, interfacing and calibration. The rotation of the stab trim wheels and movement of the stab trim indicator tabs will be discussed.

This article is one of several that pertain to the conversion of the OEM throttle quadrant. A summary page with links can be viewed here: OEM Throttle Quadrant.

Update

on 2018-04-11 01:08 by FLAPS 2 APPROACH

This article was not able to be published at an earlier time because of issues with confidentiality and potential patents. The article has been re-written (March 2018).